The Kurdish Language and Literature

Discover The Kurdish Language and Literature*

Kurdish is the language of more than twenty million Kurds living in a vast unbroken territory.

Kurdish belongs to the family of Indo-European languages and the Irano-Aryan group of this family.

The Iranophone tribes and peoples of Central Asia and the bordering territories began moving towards the Iranian plateau and the littoral steppes of the Black Sea at the turning point of the second and first millennium B.C.

As these tribes and peoples invade the area, they assimilate and give their language and their name to other Irano-Aryan peoples already present on the land. Some refuse total assimilation. Even today there are fairly large pockets of non-Kurdophone Kurds living in the Kurdistan of Turkey, Iran, and Iraq.

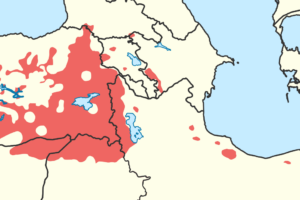

Kurdish, the language of the Kurds, which belongs to the north-western group of Irano-Aryan languages has never had the opportunity to become unified and its dialects are generally separated into three groups with distinct similarities between them.

The biggest group, as regards the number of people who speak it, is the northern Kurdish, commonly called “Kurmanjî”, spoken by the Kurds living in Turkey, Syria, the USSR, and by some of the Kurds living in Iran and Iraq. This language is also spoken by 200,000 Kurdophones settled around Kabul, in Afghanistan.

This group gave birth to a literary language.

The central group includes the Kurdish spoken in the northeast of Iraq, where it’s called “Soranî” and the dialects of the neighboring areas, beyond the Zagros, in Kurdistan of Iran. This group also gave birth to a literary language.

There has always been an intellectual elite amongst the Kurds who, for centuries, expressed themselves in the conqueror’s language. Numerous Kurdish intellectuals wrote just as easily in Arabic and Persian as in Turkish. This is shown in the XIIIth century by the Kurdish historian and biographer, Ibn al-Assir, who wrote in Arabic, whilst Idris Bitlisi, a high Ottoman dignitary, of Kurdish Origin, wrote the Hesht Behesht (The Eight Paradises) in 1501, which recounts the first story of the eight first Ottoman sultans, in Persian. Prince Sharaf Khan, sovereign of the Kurdish principality of Bitlis, also wrote his “History of the Kurdish nation”, at the end of the XVIth century, a brilliant medieval source on the history of the Kurds, in Persian.

It’s difficult to date the origin of Kurdish literature. Nothing is known about the pre-Islamic culture of the Kurds. Moreover, only some of the texts have been published and it’s not known how many disappeared in the torment of endless conflicts which have been occurring on Kurdish territory for several centuries.

The first well-known Kurdish poet is Ell Herirl, who was born in 1425 in the Hakkari region and died around 1495. His favorite subjects are already those which his compatriots will treat most often: love of the fatherland, its natural beauties, and the charm of its girls.

Kurdistan, in the XVIth century, is a battlefield between the Persians and the Turks. The Ottoman and Persian Empires were permanently formed and, at the beginning of the second half of the century, stabilized their borders, in other words, they shared the territory of the Kurds, Kurdistan.

The first famous literary Kurdish monuments date from this epoch. They are born man and Persian at the same and in opposition to the consolidation of Otto’s neighbors.

The most famous poet from the end of the XVIth and beginning of the XVIlth century is the sheik Ehmede Nishani, known as Melaye Jeziri.

He was born in Jezire Bohtan, and like many well-read people of the time, he knew Arabic, Persian, and Turkish well. He was also influenced by Arabo-Persian literary culture. His poetic work of more than 2,000 verses, has remained popular and is still republished regularly.

He traveled a lot and made numerous disciples, who tried to imitate their master by adopting his language, which from then on became the literary language.

Gradually the feeling of belonging to the same entity develops amongst the Kurds. This epoch will see the birth of the poet Ehmedi Khani, a native of the Bayazid, who defines in his Mern-o-Zin, a long poem of more than 2,650 distiches, the elements of Kurdish independence.

In the XIXth century, following the general expansion of national liberation movements at the heart of the Ottoman empire, although strongly tinged with tribalism, a Kurdish national movement slowly developed. A new literature blossoms with a certain delay due to distance and isolation. The authors who had received a classical education during their youth, given at a high level in the Imedrese’, the Koranic schools, know Arabic and Persian well. The themes and images of their poetry are inspired, to a large extent by the Persian tradition, but the poets display great imagination in the renewal of symbols and the musicality of verse.

This poetry has firstly a religious tonality, – this is the epoch of the blossoming of mystic brotherhoods – but it is the patriotic and lyrical poets who have the most success. Mela Khidri Ehmedi Shaweysi Mikhayill, better known as Nali is the first great poet to write his poetry mainly in central Kurdistan.

The birth of the press accompanied the progress of the Kurdish national movement and the first review, with the significant name “Kurdistan” appeared in Cairo, Egypt, in 1898. In the XXth century, despite being the object of persecution, the Kurdish national movement didn’t stop developing. The outbreak of the First World War and its consequences radically changed the situation of the Kurds.

The Kurds had lived up until then in multi-cultural and multi-lingual societies. At the end of this war, the Kurds find themselves divided between four states: Turkey, Persia, Iraq, and Syria, legally sovereigns but politically subordinated to the world game of superpowers. These states very quickly found themselves confronted with the problems of the diversity of languages. The literary production of the Kurds and the development of the language will from now on be dependent on the freedoms they acquire in each of the states, which share their territory.

Iraq, under British mandate, recognizes a minimum of cultural rights to its Kurdish minority. Although the latter only comprises 18% of the total Kurdish population, the center of the Kurdish cultural life is transported to Iraq, where production will develop from the second half of the 1920s. The Kurds came out of isolation and contact with the West – translation of Pushkin, Schiller, Byron, and particularly Lamartine – completely changed the basic ideas in the poetic field.

The beginning of modernity distances poetry from its traditional paths and if, in the first stage, the poems keep their classical form, innovation lies in their content, the Kurdish population – loses their freedom and production dries up. They are forced to publish their works abroad or to go into exile.

In Turkey, after the military success of Mustafa Kemal against Greece, a new treaty signed at Lausanne in 1923, confirmed Turkish sovereignty over a large part of the Kurdish territory and more than 52% of the total Kurdish population. This treaty guaranteed “non-Turks” the use of their language. A few months later, in the name of State unity, Mustafa Kemal violated this clause by banning the teaching of Kurdish and its public use. He deported most of the intellectuals. The Kurds became the “mountain Turks”, living in “Eastern Anatolia” or in the “East”. All the traditions, even the dress, all the groups, even the song and dance were abolished in 1932. After the Second World War, the Turkish regime between 1950 and 1971 gave itself a tinge of bourgeois democracy, and the use of the Kurdish language was authorized again. A new Kurdish intelligentsia formed. The military coups Xetat of 1971 and 1980 restored the policy of repression and massive deportations towards the west of Turkey. The teaching of Kurdish and publications in this language are strictly forbidden today.

In Iran, where more than a quarter of the Kurdish population live, the authorities conduct a harsh policy of assimilation of their Kurdish minority. All Kurdish publications and teaching of the language are forbidden.

The great period of Kurdish literature in this area is that of the Republic of Kurdistan which only lasted eleven months at the end of the Second World War. Despite its brevity, it provokes a remarkable development in Kurdish literature. Numerous poets emerged, such as the poets Hejar and Hemin. The repression that followed the fall of the Republic forced the intellectuals to go into exile, mostly in Iraq. In February 1979, a revolution of the people expelled the monarchial regime but the Islamic government which replaced it was also unwilling to accord national rights to its Kurdish minority.

Under pressure from Kurdish revolutionaries gathered around the much missed Dr. Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, whose memory is engraved in the depths of our hearts, who demand incessantly the recognition of their language and their culture, the Iranian authorities are forced to tolerate the publication of various Kurdish works. If all literary creation remains forbidden, censorship authorizes the publication of monuments from the Kurdish literature of the XIXth century, some of which will be translated into Persian. Manuscripts depicting the history of Kurdish dynasties are finally published and dictionaries, grammar books, and encyclopedias by Kurdish personalities who marked their epoch, religious or not, appear in Kurdish and Persian.

The Kurdish literary life in Iraq suffered the repercussions of the failure of the long Kurdish insurrection and the pitiless war between Iran and Iraq.

The Kurdish intellectuals choose the path of exile and take refuge in most of the Western countries and, remarkably, they will be at the source of a real renaissance of the “Kurmanjî” literature, strictly forbidden in Turkey and Syria. Supported by several hundred thousand Kurdish emigrant workers, the Kurdish intellectuals gathered together and made every effort to promote their language. Poets and writers print their works firstly in the reviews published by Kurdish publishing houses in Sweden. The Swedish authorities which favor the cultural development of emigrant communities, allocate the Kurds – they are 12,000 – a relatively large publication budget. Around twenty newspapers, magazines, and reviews came out from the end of the 1970s. Children’s books, alphabet primers, and translations of historical works on the Kurds … come out. Literary creation is encouraged. M. Emin Bozarslan brings out charming children’s stories and Rojen Barnas collections of poems, whilst the journalist Mahmut Baksi, a member of the Swedish Writers’ Union, publishes a novel and stories for children in Kurdish, Turkish, and Swedish, Mehmet Uzun brings out two realist novels.

Two hundred titles have appeared in ten years. It’s the biggest Kurdish literary production, outside Iraq. But it’s in France, in Paris, that a dozen courageous, dynamic, and very nice Kurdish intellectuals, in February 1983, created the first Kurdish scientific institute in the West. Six years later, more than three hundred Kurdish intellectuals, living in various European countries, and in America and Australia, have joined the Institute to help carry out its action of safeguarding and renewing their language and their culture.

The Institute publishes reviews in Kurdish, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and French. A “Bulletin de liaison et d’information” (Monthly Bulletin of Contact and Information) publishes a press review about the Kurdish issue and gives information about the activities and projects of the Institute. It’s to the credit of the Institute that they were the first to encourage the development of the “Zaza / Dimlî’ dialect, spoken by about three million Kurds in Turkey. Finally, the Institute gathers together Kurdish writers, linguists, and journalists from the diaspora, twice a year to study together the problems of modem terminology.

This new blossoming of Kurdish intellectuals, poets, and writers illustrates most strikingly the parallelism between cultural freedom and development.